by Bailey Dolenc

The names Degas, Monet, and Renoir spring to mind when considering celebrated Impressionist painters of the late nineteenth-century. Ordinarily when most think of Impressionists, male artists are usually the first or only names posed.

Mary Cassatt self portrait-1880

But what about the ladies? Fascinating women artists such as Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, Marie Bracquemond, Eva Gonzales, and Suzanne Valadon were praised by Impressionists based on their talents which led to exhibiting their artworks alongside those of male artists. Unlike society, Impressionism was not monopolized by men, but remarkably influenced by women.

Mary Cassatt fits into the present world without seeming out of date. There is an inner conviction about her work which asserts itself over and above any specific limitations of time and place… She is by all odds the best woman painter America has ever produced. -Frederick Sweet, Curator of American Painting and Sculpture, Art Institute of Chicago, 1954

Neither a Parisian nor a man, the odds that Mary Cassatt would participate in the Impressionist movement were low. Cassatt, born in 1844 into a wealthy family in Pittsburgh, was unlikely to become an expatriate living abroad painting among men. But instead of complying with society by marrying, she followed her passion and enrolled in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, one of the first art institutions in America to accept young women. After formal training, Cassatt traveled throughout Italy, Spain, and France, giving her a chance to study the Old Masters while creating her distinct style. Her paintings became a synthesis of traditional techniques and modern narratives, focusing on the mysterious lives of women.

This integration is apparent in a series of paintings that depict women in theater settings. Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge (c. 1879), presents a young woman in a theater balcony donning a feminine, coquettish dress, seemingly to attract attention. First introduced to Europe in the seventeenth century, the folding hand-held fan from East Asia was popular among ladies through the 1950s. Here the young woman holds a fan in her gloved hand, perhaps signaling her modesty and wealth. In the Loge (c. 1880)

This integration is apparent in a series of paintings that depict women in theater settings. Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge (c. 1879), presents a young woman in a theater balcony donning a feminine, coquettish dress, seemingly to attract attention. First introduced to Europe in the seventeenth century, the folding hand-held fan from East Asia was popular among ladies through the 1950s. Here the young woman holds a fan in her gloved hand, perhaps signaling her modesty and wealth. In the Loge (c. 1880) portrays a lady peering through opera glasses from the balcony, supposedly observing other theater-goers. Her attire speaks volumes; wearing a high collared, long-sleeved black frock, it seems that she is a woman who would rather see than be seen. Cassatt portrays timid young girls in a third theater portrait, La Loge (c. 1882).

portrays a lady peering through opera glasses from the balcony, supposedly observing other theater-goers. Her attire speaks volumes; wearing a high collared, long-sleeved black frock, it seems that she is a woman who would rather see than be seen. Cassatt portrays timid young girls in a third theater portrait, La Loge (c. 1882).  The girls are a combination of the previous two; they appear demure yet dressed for display. Adorned in elegant gowns, long gloves, and holding a fan and bouquet, the young ladies are there to present themselves, however, the figures press close together, further illustrating their age and social inexperience. Upon spotting a Degas painting in Paris that portrayed ballet dancers, Mary Cassatt stated, “I saw art as I wanted to see it… I began to live.” Cassatt had discovered a passion for painting women, depicting the subtleties of their private and public lives. Degas, with whom she had a forty-year friendship, urged Cassatt to join the Impressionists after viewing her entry in a Paris salon exhibit. Although she was an expatriate woman artist living in Paris, throughout her life she encouraged the interest of art and helped develop art schools in America. As the only American and one of only three women to exhibit with the Impressionists, Mary Cassatt made her mark in the world of Art and Men.

The girls are a combination of the previous two; they appear demure yet dressed for display. Adorned in elegant gowns, long gloves, and holding a fan and bouquet, the young ladies are there to present themselves, however, the figures press close together, further illustrating their age and social inexperience. Upon spotting a Degas painting in Paris that portrayed ballet dancers, Mary Cassatt stated, “I saw art as I wanted to see it… I began to live.” Cassatt had discovered a passion for painting women, depicting the subtleties of their private and public lives. Degas, with whom she had a forty-year friendship, urged Cassatt to join the Impressionists after viewing her entry in a Paris salon exhibit. Although she was an expatriate woman artist living in Paris, throughout her life she encouraged the interest of art and helped develop art schools in America. As the only American and one of only three women to exhibit with the Impressionists, Mary Cassatt made her mark in the world of Art and Men.

Berthe Morisot self portrait-1872

Equally intriguing and as improbable to become a painter, Berthe Morisot nevertheless showed her paintings in seven of the eight Impressionist exhibits and perhaps inspired a fellow artist to compose a famous series of paintings. Morisot’s beginnings were by no means modest; the French bourgeois family she was born into in 1841 lived on an annual income of eight thousand Francs while a typical worker only earned three Francs a day. Her interest in the arts was supported by her mother Cornelie early on, studying piano with Stamaty, drawing lessons with Guichard, and later painting en plein aire with Corot. Edma, Morisot’s sister, shared her artistic talents and participated in lessons until Cornelie urged her to marry, a notion that was expected of both girls. Academic painter Joseph Guichard realized the Morisot sisters’ capabilities and wrote to their mother, “They will become painters. Are you fully aware of what that means? It will be revolutionary–I would almost say catastrophic–in your bourgeois society.” Thus, Edma was married and Berthe closely was chaperoned throughout her career as a painter.

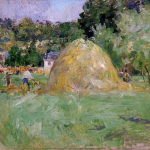

Considering the Louvre did not exhibit paintings by women in the 1850s, Morisot studied classics by men and made friends with young male artists, learning their techniques. As a young French woman she was denied any formal training; however, at age nineteen Morisot was one of few artists transporting new portable paints and a smaller canvas to the outdoors with Camille Corot. Painting en plein aire with her sister and Corot lead to possibly her most innovative and inspiring series of paintings: haystacks.

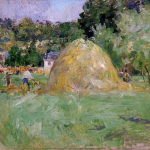

The Small Haystack 1882

haystacks a bougival 1883

Haystack, c. 1883

Unbeknownst to many, Morisot seems to be the pioneer of the popular haystack series many associate with Claude Monet. She captured light which illuminated the haystacks at different times in the day only a few years before Monet began to paint them.

Out of all of the influences in Morisot’s life, Edouard Manet was the most enduring. Introduced to the decade older artist in 1868, Morisot soon became a regular model for Manet’s paintings despite her social standing. Posing for eleven different portraits, her chaperone and mother Cornelie became anxious for her daughter’s appropriate role as a wife. Manet eventually proposed that she marry his younger brother Eugene, a trained lawyer with sufficient wealth to support Morisot’s painting career and independence. More importantly, marrying Eugene protected her reputation and the Morisot name. Remaining true to her calling, she continued to paint and encouraged the gathering of Impressionist painters at weekly dinner parties which she hosted.

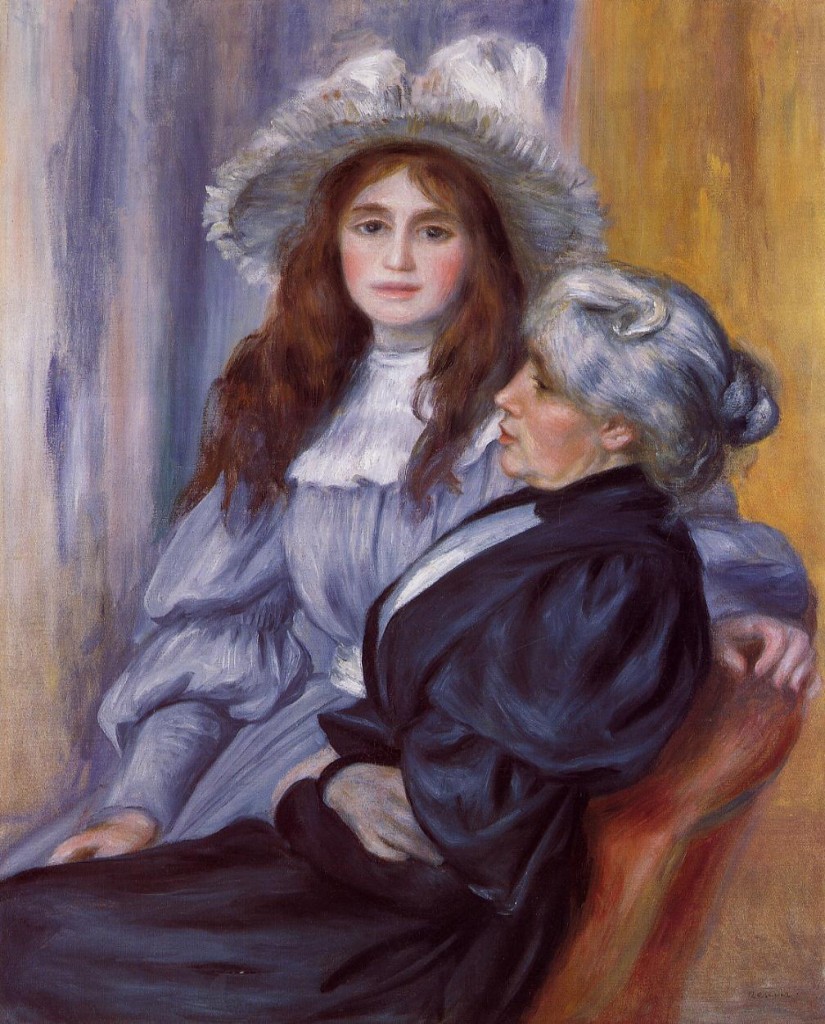

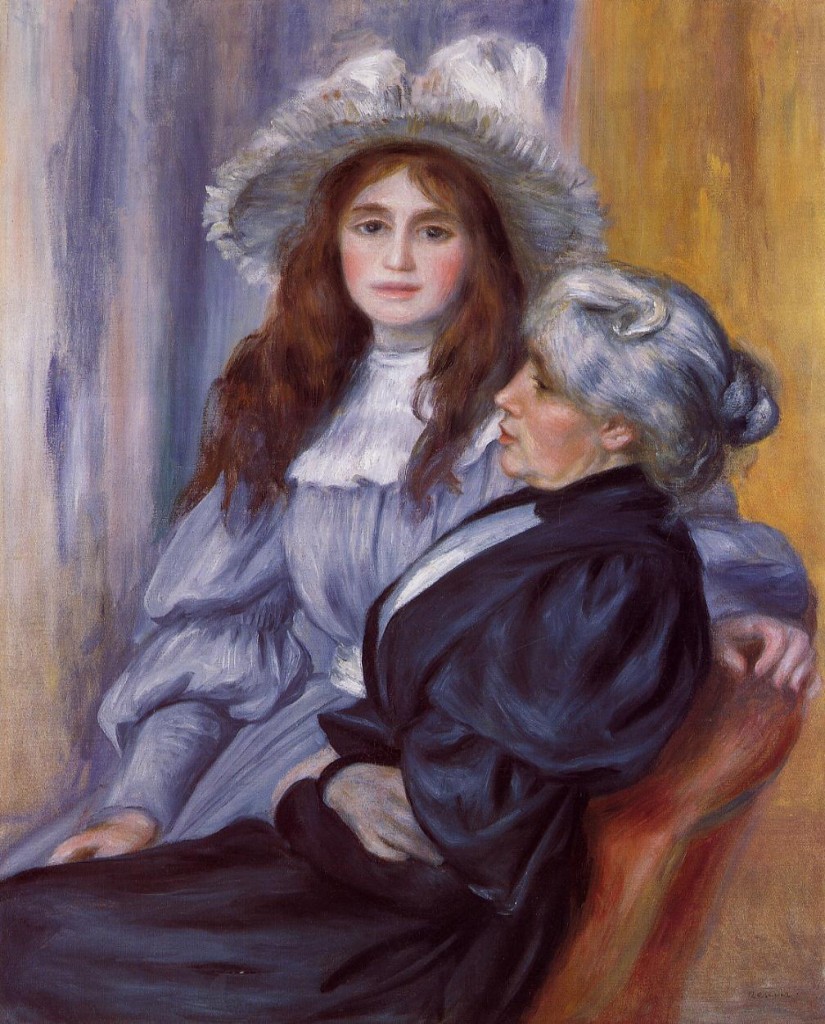

Berthe Morisot and Her Daughter, Julie Manet, c. 1894

Morisot’s subject matter shifted when her daughter Julie was born. Suddenly, her paintings more often surrounded that of women, children, and the relationship shared between them. However, it appears that her favorite muse was her daughter, for she painted her incessantly. Eugene Manet and His Daughter at Bougival, Julie Manet et son Levrier Laerte, and Julie Reveuse portray her daughter at various ages.

Eugene Manet and His Daughter at Bougival, c. 1881

Julie Manet et son Levrier Laerte, c. 1893

Julie Reveuse, c. 1894

Around 1880 the original group of Impressionist painters began to split and the growing fame of post-Impressionist painters like Cezanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh ultimately overshadowed that of their predecessors. The accomplishments of both Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot opened the doors for the next generation of women artists. Because of these remarkable female painters, male artists now believe in a woman’s artistic capacities, and in Monet’s case, learn from them.

Sources

Brown, Katie, “Rebel with a Cause,” Louisville Magazine 56.7 (2005): 15.

Fayard, Judy, “Making the Right Impression,” Time Europe 159.20 (2002): 56.

Harmon, Melissa Burdick, “Monet, Renoir, Degas… Morisot:

The Forgotten Genius of Impressionism,” Biography 5.6 (2001): 98.

May, Stephen, “Mary Cassatt, Genteel Powerhouse,” World & I 14.3 (1999): 96.

Parney, Lisa Leigh, “Impressionist and Modern Woman,”

Christian Science Monitor 91.68 (1999): 19.

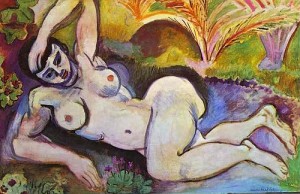

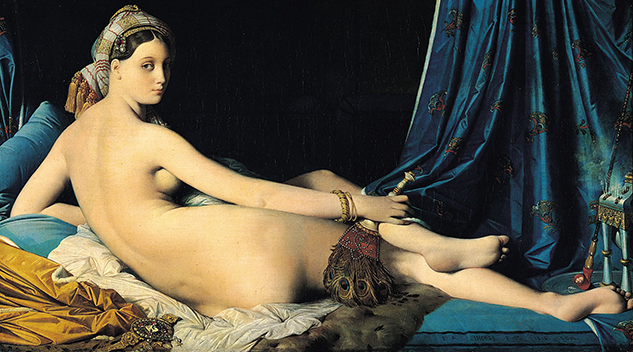

The Grande Odalisque by Ingres and Olympia by Manet, are of the same subject, a nude woman. The paintings are modeled after Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538).

The Grande Odalisque by Ingres and Olympia by Manet, are of the same subject, a nude woman. The paintings are modeled after Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538).

In 1863, Manet created his female nude Olympia as a harshly painted stiff figure with a callous gaze towards the viewer. As opposed to Ingres’s painting, Manet placed Olympia in a quite unwelcoming pose, with her genitals covered, legs tightly crossed, and an unashamed body language.

In 1863, Manet created his female nude Olympia as a harshly painted stiff figure with a callous gaze towards the viewer. As opposed to Ingres’s painting, Manet placed Olympia in a quite unwelcoming pose, with her genitals covered, legs tightly crossed, and an unashamed body language. The uses of color in each painting evoke contrasting moods. Olympia’s flesh tone is a stark white that blinds the eye, whereas the Odalisque’s flesh is of a much warmer tone and thus creates a more inviting environment. The backgrounds, sheets, pillows, and jewelry either invite the viewer into the painting with warm colors and soft, silky fabrics such as in The Grande Odalisque, or dismiss the viewer with flat surfaces and harsh bright colors as in Olympia.

The uses of color in each painting evoke contrasting moods. Olympia’s flesh tone is a stark white that blinds the eye, whereas the Odalisque’s flesh is of a much warmer tone and thus creates a more inviting environment. The backgrounds, sheets, pillows, and jewelry either invite the viewer into the painting with warm colors and soft, silky fabrics such as in The Grande Odalisque, or dismiss the viewer with flat surfaces and harsh bright colors as in Olympia.

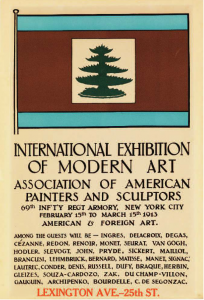

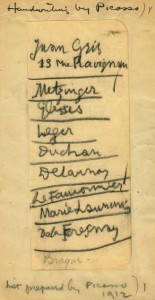

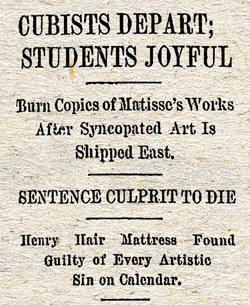

Many other artists seem to have been similarly moved by Cezanne’s work. After viewing a major Cezanne exhibition in 1907, George Braque and Pablo Picasso were inspired to create paintings of a cubic nature.

Many other artists seem to have been similarly moved by Cezanne’s work. After viewing a major Cezanne exhibition in 1907, George Braque and Pablo Picasso were inspired to create paintings of a cubic nature.