by Bailey Dolenc

The visual arts in today’s world are experiencing an unprecedented upheaval, engendering new perceptions of art that will doubtless make a mark on world history. Art has never before been this accessible, radical, and exciting. Although the expanding art world offers plentiful benefits, there are several issues that arise with burgeoning technology, auction house practices, the challenges of branding, the exclusivity of major art centers, and fraudulent art. These issues will be discussed with the intent of providing realistic solutions for the developing art world.

The visual arts in today’s world are experiencing an unprecedented upheaval, engendering new perceptions of art that will doubtless make a mark on world history. Art has never before been this accessible, radical, and exciting. Although the expanding art world offers plentiful benefits, there are several issues that arise with burgeoning technology, auction house practices, the challenges of branding, the exclusivity of major art centers, and fraudulent art. These issues will be discussed with the intent of providing realistic solutions for the developing art world.

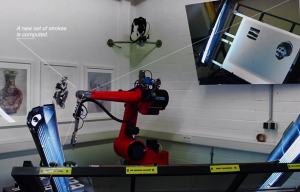

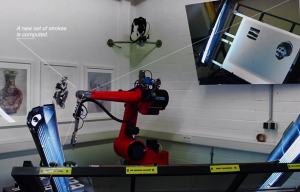

See the video “David Paints Like A Machine”

It is evident that art making has progressed with the rise of technology. One of the most pressing issues for future artists is machine intelligence and a machine’s ability to create, seemingly flawlessly. Although, can true human creativity really be programmed? This concept causes one to question, what constitutes an artist and, what is art? Likewise, the advent of the Internet has altered the ways in which viewers experience artworks. Once the predominant arena for viewing art and bustling with activity, museums have become a graveyard for accomplished artists, while providing a brand for those artists to establish themselves. Consequentially, museums can be considered as a sort of enigma. As the popularity of museums declines and the need for new art increases, living artists are choosing alternative venues to display their works such as in studios, galleries, and most recently, on the Internet.

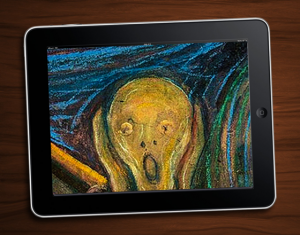

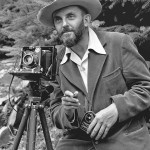

Image by Dr. Beth Harris & Dr. Steven Zucker

Current technology is capable of capturing fine detail, authentic coloring, and copious information regarding an artwork, allowing cyber museums to offer the ability to view art without leaving home. However, it can be disputed that the experience of being in the presence of an artwork, as opposed to viewing one digitally, holds far more advantages. Context is especially important when considering this argument. Museums carefully consider the context in which a piece of art is placed, grouping artworks in terms of culture and time period. When context is eliminated, the viewer is denied the emotion and understanding that arises when examining a piece in person, especially one of a grand scale. To circumvent this concern while gratifying the need for accessible art, museums must rely on cutting-edge technology to both remain relevant in the art world and satisfy the need for real-life experiences.

Whereas museums serve as educational institutions, auction houses often ignore an artwork’s context altogether. The purpose of the auction house is to sell art at the highest price. This notion ultimately disregards the skills of artists and the meanings they wish to convey in their artworks. The art collectors and dealers who attend auctions are primarily concerned with aesthetics and branding; collectors often wish the art for which they bid to reinforce their social status, while dealers’ interests lie in profits. A collector’s purchased artwork must be both pleasing to the eye and have its own reputation, or in other words, brand. Otherwise, there are scant reasons for the collector to make the purchase. Dealers rely on branding, as an artwork’s or artist’s reputation determines its selling value. To better represent context in an auction house setting, it is ideal that the community as a whole better educate themselves on the artworks for which they are bidding.

Living artists can successfully establish themselves in the art world in terms of the brand with which they associate. However, branding in itself is a predicament for contemporary art. As earlier discussed, museums and auction houses act as brands; in addition, old master artists are also brands, as their reputations have endured over time. Although branding seems like an invaluable tool for selling art, unidentified artists find themselves in a quandary. For those lacking a brand to support them, selling their work can be an arduous task, as an artist’s anonymous status can cause the public to judge their art as unreliable. Emerging artists rely on the prestige of galleries, at which a collector might attend, to succeed. In some special cases, a keen-eyed, eminent collector may establish an artist by purchasing their work, creating yet another brand in the art world. Nevertheless, brands remain in an elite clique that is seemingly impenetrable for the majority of emerging artists. While continuing to acknowledge the importance of branding, what is needed is perhaps a growth and migration of brands to smaller cities. In theory, this would ultimately give artists living outside of major art centers greater opportunity, and possibly promote diversity in popular art.

London and New York are considered major art centers, reeling in artists, collectors, dealers, and critics from around the globe. As a result, numerous other cities are forced to sacrifice talented, artistic minds to these art world hot spots. In order to lessen artist flight and encourage more diversity in the arts in the future, with the help of brand migration, alternate cities must entrench themselves into the arts via branded galleries, auction houses and art museums. For this plan to be successful, these cities must be recognized as distinct art centers by artists and their contemporaries.

Also in need of assuaging is the growing issue of fraudulent art. Although brands provide security and trust for buyers, unfortunately, they also create opportunity for forgery.  The brand of a master artist can act as a disguise for copies or fakes. Given that auction participants often base their decisions on branding, it is inevitable that some artworks are actually frauds. These posing masterpieces can cause problems for all; auction attendees bid unnecessarily high and private buyers likely make colossal, miscalculated purchases. Meanwhile, galleries, auction houses, and museums put their brands at risk, all due to spurious artworks. In this particular case, technology is a great advantage and absolutely necessary. Today, investigators use various methods from x-ray to craquelure. Nevertheless, fraudulent art may still be a concern in the future, for it is possible that as art specialists learn to descry a fake, con artists will concurrently find ways to outsmart in order to continue their trade.

The brand of a master artist can act as a disguise for copies or fakes. Given that auction participants often base their decisions on branding, it is inevitable that some artworks are actually frauds. These posing masterpieces can cause problems for all; auction attendees bid unnecessarily high and private buyers likely make colossal, miscalculated purchases. Meanwhile, galleries, auction houses, and museums put their brands at risk, all due to spurious artworks. In this particular case, technology is a great advantage and absolutely necessary. Today, investigators use various methods from x-ray to craquelure. Nevertheless, fraudulent art may still be a concern in the future, for it is possible that as art specialists learn to descry a fake, con artists will concurrently find ways to outsmart in order to continue their trade.

Issues like the aforementioned technology, auction house practices, branding, major art centers, and fraudulent art are currently reshaping the collective understanding of the art world. Thus, the future for the visual arts is at stake. If these growing concerns regarding the arts in the future are to be eradicated they must first be acknowledged by those working in the arts today; it would then be possible to spread awareness, and ideally, work towards creating an uncorrupted atmosphere in which artists can express their talents.

Sources

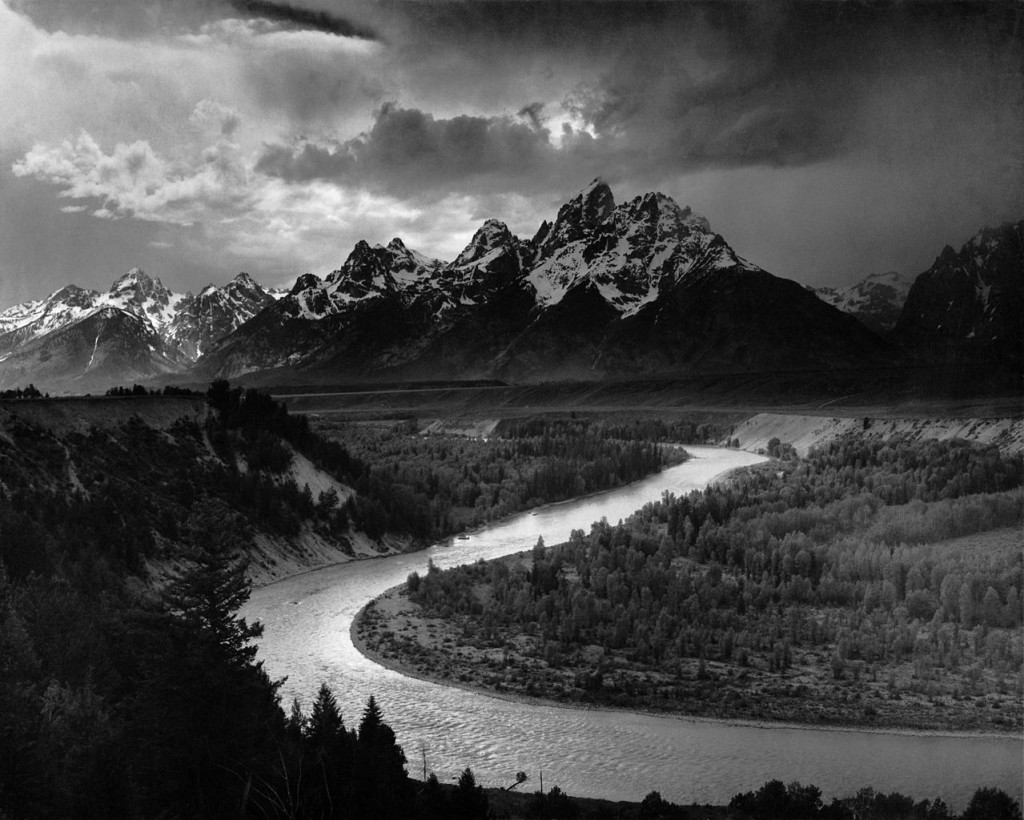

National Archives and Records Administration: Public Domain.

Ansel Adams is one of the most influential and innovative early photographers of the United States. His black-and-white photographs of the great American West have inspired many. Even more inspirational to many photographers today is Adams’ Zone System, which helps the photographer find the best gradient for a picture and is an essential tool when creating black-and-white prints.

Ansel Adams is one of the most influential and innovative early photographers of the United States. His black-and-white photographs of the great American West have inspired many. Even more inspirational to many photographers today is Adams’ Zone System, which helps the photographer find the best gradient for a picture and is an essential tool when creating black-and-white prints.