by Bailey Dolenc Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Les Lauves, c. 1904-06)

Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Les Lauves, c. 1904-06)

“Painting must give us the flavor of nature’s eternity.” – Paul Cezanne

Springtime conjures in us thoughts of rebirth with the beauty of sprouting grass, blooming flowers, and green trees. Spring reminds us that all on Earth is applied to a set of rules, but is never static. As French painter Paul Cezanne put it, “Nature is always the same, and yet its appearance is ever changing.” Similarly, fundamental painting techniques existed yet Cezanne discovered a way to deviate from his predecessors, forever altering his contemporaries’ perceptions and use of their medium. But before creative genius blooms, it must be planted.

Cezanne’s painting revolution seems to have begun around the year 1873 when long-time friend and colleague Camille Pissarro invited Cezanne to Pontoise. Here, the two artists painted en plein air, often together on the same subject. Cezanne learned Impressionist color theory and painting techniques which taught him that painting is based on visual perception of nature that can be translated by use of painterly means. With the tools acquired from Pissarro and the Impressionists, a springboard for his own creative techniques was built.

His understanding of the inner workings of nature reflects the time he spent living and painting in his native rural Provence. Left with a substantial fortune after his father’s passing in 1886, Cezanne was able to concentrate on his work without the everyday pressure of selling paintings to make a living. Most importantly, working far from the hustle and bustle of Paris enabled him to create a distinctive art form all his own. Deviating from Impressionist principles, Cezanne abandoned the single vanishing point and established depth with overlapping, interlocking layers. This technique ultimately gave density to his objects in a somewhat cubic structure, giving way to a simultaneous feeling of tension and balance.

Cezanne has managed to strip pictorial art of all the mold accrued in the course of time . . . If — as I dare hope it will — a tradition is born of our times it will be born of Cezanne. -Paul Serusier, Mercure de France, 1905

In November of 1895, one hundred and fifty of Cezanne’s paintings were exhibited at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery in Paris. After viewing Cezanne’s works, the Nabis, a group of artists who believed that art reflects an artist’s synthesis of nature and who had a major influence on art produced in France at the time, proclaimed themselves Cezanne’s disciples. Their praise of Cezanne’s work is represented quite literally in Maurice Denis’s Homage a Cezanne (c. 1900). From left to right, Vuillard, Denis, Serusier, Ranson, Roussel and Bonnard discuss a still-life by Cezanne.

In November of 1895, one hundred and fifty of Cezanne’s paintings were exhibited at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery in Paris. After viewing Cezanne’s works, the Nabis, a group of artists who believed that art reflects an artist’s synthesis of nature and who had a major influence on art produced in France at the time, proclaimed themselves Cezanne’s disciples. Their praise of Cezanne’s work is represented quite literally in Maurice Denis’s Homage a Cezanne (c. 1900). From left to right, Vuillard, Denis, Serusier, Ranson, Roussel and Bonnard discuss a still-life by Cezanne.

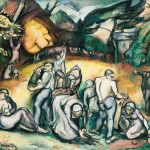

The influence of Cezanne’s innovative paintings then seems to have spread like wildfire across the minds of his fellow painters in order to give birth to regenerated art forms. Inspired by Cezanne’s Post-Impressionist paintings, Paul Gauguin began to paint in parallel brushstrokes, condense lines into force fields, outline objects, and give more volume to his figures. Fuller forms in Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings are reminiscent of Cezanne’s Trois Baigneuses (c. 1879-82), which was purchased by Henri Matisse from Vollard in 1899.

In 1936, Matisse donated Trois Baigneuses to the Petit Palais and wrote to the museum director of the painting’s importance throughout his career: “In the thirty-seven years I have owned this canvas, I have come to know it quite well, I hope, though not entirely; it has sustained me morally in the critical moments of my venture as an artist; I have drawn from it my faith and perseverance.”

Many other artists seem to have been similarly moved by Cezanne’s work. After viewing a major Cezanne exhibition in 1907, George Braque and Pablo Picasso were inspired to create paintings of a cubic nature.

Many other artists seem to have been similarly moved by Cezanne’s work. After viewing a major Cezanne exhibition in 1907, George Braque and Pablo Picasso were inspired to create paintings of a cubic nature.

Picasso’s Tables and Loaves and Bowl of Fruit (c. 1909) can be perceived as a salute to Cezanne due to the fragmented table edges, voluminous forms, soft tones, and aerial viewpoint. It is believed that Cubism was born of Cezanne’s influence; in the first stage of Cubism, Braque and Picasso embraced Cezanne’s formative method, however, eschewed his color palette. Instead, darker, earthier tones are used in paintings such as The Poet (Picasso, c. 1911) and Violon et Cruche (Braque, c. 1910).

Even the Fauvists were swept away by the wave Cezanne had created; the vivacious coloring once present in their paintings began to diminish. Cezanne’s impression on Fauvist painters can be found in a quote from Fauvist Othon Friesz: “We returned to laws of composition, and of volume — Fauvism was sacrificed . . . there was no other way to get out of the trough of Impressionism.” When comparing Friesz’s La Ciotat (c. 1907) with his later Travail a L’Automn (c. 1908), Cezanne’s influence is apparent; the strange yet lively colors transform into more natural hues, as vibrant pops of color are later outlined with dark tones.

The myriad Cezanne followers grew immeasurably since exhibiting his paintings at Vollard’s Paris gallery in 1895. Cezanne was able to express in his art a personal deviation from his Impressionist beginnings, attracting painters of all disciplines. As his colleagues learned and departed from his techniques, new art forms were born, providing an exciting exploration of the art of painting. Whether it be street art or paint on canvas, Cezanne’s legacy can still be observed in today’s art world.

The myriad Cezanne followers grew immeasurably since exhibiting his paintings at Vollard’s Paris gallery in 1895. Cezanne was able to express in his art a personal deviation from his Impressionist beginnings, attracting painters of all disciplines. As his colleagues learned and departed from his techniques, new art forms were born, providing an exciting exploration of the art of painting. Whether it be street art or paint on canvas, Cezanne’s legacy can still be observed in today’s art world.

Sources

Bocola, Sandro. The Art of Modernism: Art, Culture, and Society from Goya to the Present Day. Translated by Catherine Schelbert and Nicholas Levis. Munich: Prestel Verlag, 1999.

Parsons, Thomas and Iain Gale. Post-Impressionism: The Rise of Modern Art 1880-1920. London: Studio Editions Ltd, 1992.